As I write this blog post, I find myself at the helm of two teams within a renowned Dutch financial institution, with its central hub in Utrecht. The diversity within my one team (refer to picture below) is nothing short of remarkable; comprising seven individuals from across the globe, including myself, we represent a tapestry of cultures: Spanish, Italian, Pakistani, Bangladesh, German, Dutch and South African. This blend of nationalities was something I never envisioned, yet it has been an enriching journey over the past few months.

While working in South Africa, my exposure to diverse cultures was limited. This changed significantly after my wife and I relocated to the Netherlands back in 2021. Suddenly, I found myself collaborating with individuals from various backgrounds, which heightened my awareness of the cultural nuances involved.

I recall a specific moment when I began collaborating with a new colleague from India. I observed behavioral patterns unfamiliar to me, which initially led me to form a bias (unconsciously). Over time, I decided that these differences were likely due to personality rather than cultural background, and I came to accept that we might never see eye to eye.

To effectively navigate cultural diversity, an acquaintance recommended ‘The Culture Map’ by Erin Meyer. The book was profoundly insightful, and I completed it within a short period of time. It empowered me to understand my colleagues better and fostered a deep appreciation for cultural differences, both in the workplace and beyond. As the book aptly puts it, it enabled me to ‘decode other cultures and avoid easy-to-fall-into cultural traps’.

Before delving into the main content of this blog post (see table of contents below), I’d like to share some scenarios I’ve encountered in the past. My hope is that by the conclusion of this post, you’ll be equipped with the knowledge to navigate similar situations in the future.

- After presenting my work to my British boss, he responded with a noncommittal ‘very interesting.’ I left the meeting with a lingering doubt about whether he truly appreciated my presentation or not.

- In an effort to better manage my time at work, I decided to reserve slots in my calendar for ‘focus time,’ ensuring uninterrupted work on my priorities. However, just as I entered this sacred period of concentration, my Indian colleague called me out of the blue, despite my ‘busy’ status on MS Teams. I immediately dropped what I was doing, sensing urgency in his voice. It turned out he wanted to catch up and discuss a matter that, upon reflection, could have waited until next week. After the call, I couldn’t help but question why I had allowed someone else to disrupt my focus time. Why hadn’t my colleague respected my schedule and arranged a meeting for a more appropriate time?

- Upon joining a new team, I began collaborating with an Italian colleague. As we attended several meetings together, I observed that he often displayed a very direct manner of communication, which sometimes came across as disrespectful. He frequently voiced complaints and seldom offered potential solutions. Over time, this behavior began to irritate me, as it seemed to affect the overall team morale.

- I joined a meeting with a predominantly Dutch team. As the discussion progressed, it became increasingly heated, and it was evident that two individuals were engaged in a spirited debate. From my vantage point, it seemed like a conflict was unfolding. Despite this, I chose to remain silent, not wishing to exacerbate the situation by inserting myself into the heated exchange.

- In a meeting with predominantly Indian colleagues, I noticed that I had been dominating most of the conversation, filling the awkward silences during the call. This led me to question why my colleagues were not more actively engaged in our discussion, leaving me to wonder if I was the only one contributing.

- Importance of cultural awareness

- Decoding other cultures

- Advice for navigating cultural differences

- Additional insights from my team members

- Conclusion

Importance of cultural awareness

Being aware is often the first step toward positive change. When you observe carefully, cultural differences become apparent wherever you go. Since relocating to The Netherlands, we’ve had the privilege of traveling to various countries. One of our favorite aspects of travel is discovering new cultures and trying to put ourselves in the shoes of others who have a different point of reference than we do. For example, I’ll never forget the first time we visited Austria. As you can imagine, we were blown away by the landscape and the stunning mountain scenery, finding it hard to believe that this was the everyday norm for people living there. In terms of cuisine, I recall ordering a local dish—an authentic Wiener Schnitzel with lingonberry jam—and being pleasantly surprised. This unique combination has now become a go-to meal whenever I visit Germany or Austria.

The point I’m trying to make is this: What might be completely normal for an Austrian could seem strange or odd to a South African like myself. In other words, what may be considered positive in one culture may be viewed as negative in another. I’ve learned to recognize and appreciate these cultural differences, and over time, I’ve come to value the unique contributions each nationality brings to the table.

In my capacity as a team leader, I’ve come to realize that cultural diversity is a significant team strength, offering several benefits for problem-solving. In one of my teams, we’ve successfully leveraged our diverse perspectives to find an innovative solution to a problem we were addressing at the time.

However, working with different cultures isn’t always smooth sailing. I recall many prior scenarios where I found myself wondering, “Is there a way to decode other cultures?”

Decoding other cultures

Thankfully, Erin Meyer provides a framework for understanding and navigating cultural differences. In her book, she describes eight different cultural scales that can be used to create your own cultural framework, or “culture map.”

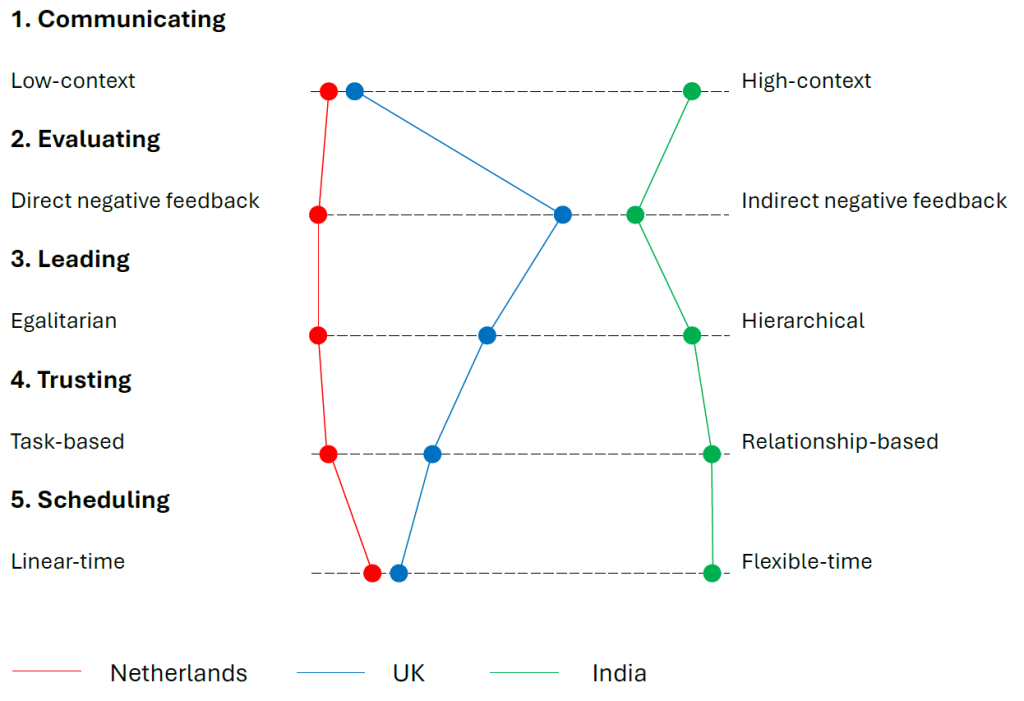

For my personal gain at work, I created a culture map in 2023, reflecting some of the main cultures I engaged with at the time: Dutch, British, and Indian. In the subsequent section, I will position and briefly explain some of the key scales (in my opinion).

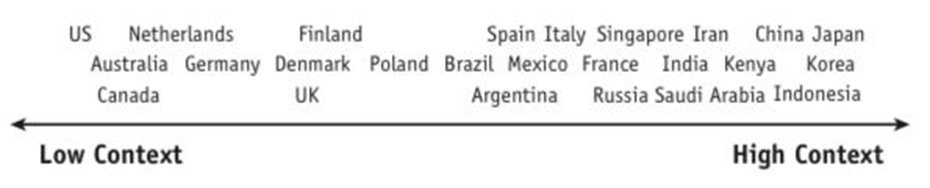

Communicating Scale

In the realm of communication, it’s essential to differentiate between low-context and high-context cultures. Low-context cultures, such as those in the Netherlands or the United Kingdom, value straightforward, clear, and explicit communication. In contrast, high-context cultures, like India, rely on a shared understanding and non-verbal cues. For instance, in Hindi, the word ‘kal’ can mean both ‘tomorrow’ and ‘yesterday,’ depending on the context. To grasp the intended meaning, one must consider the entire sentence and interpret the nuances beyond the literal words.

When working in multicultural teams, adopting low-context communication processes can help prevent misunderstandings and conflicts. However, this approach may inadvertently convey distrust to high-context team members, who value implicit understanding and trust. For instance, insisting on written documentation—a hallmark of professionalism in low-context cultures—might imply a lack of confidence in their colleagues’ reliability. To navigate this, it’s crucial to establish a mutually agreed-upon way of working that respects everyone’s cultural preferences. This agreed-upon WoW should be clearly communicated and understood by all and there should be no confusion as to why certain behavior will be the norm going forward.

Evaluating Scale

The evaluation scale is closely tied to the topic of feedback. In my previous blog post titled ‘Feedback: Your Gateway to Growth and Success,’ I briefly emphasized the importance of cultural awareness when collecting feedback from colleagues. For example, a Dutch person tends to be very direct and rarely assigns a top rating (such as ‘exceeds expectations’). On the other hand, someone from India might be more inclined to provide positive feedback, even if it means not highlighting areas for improvement. Erin Meyer highlights that what is considered constructive in one culture may be viewed as destructive in another.

At one end of the evaluation scale, we have direct negative feedback, and at the other end, we have indirect negative feedback.

Cultures located on the left of the scale tend to be very familiar with collecting and providing direct (often negative) feedback. When sharing any form of feedback—whether good or bad—they do so with complete honesty, without holding back or beating around the bush. Shortly after arriving in The Netherlands, I was told that Dutch people are extremely direct, and after living in the country for 3+ years, I can attest to this fact. Dutch and similar cultures welcome debates and disagreements, perceiving them as positive signs, while silence may be regarded as a negative sign.

Cultures located on the far right of the scale, such as Indian people, are less accustomed to direct negative feedback. They tend to avoid it, and only if absolutely necessary, will they provide it gently and often very diplomatically. Unlike Dutch people, who wouldn’t hesitate to give criticism in a public setting, Indian culture tends to handle such situations more delicately.

However, it’s worth sharing that I encountered a contrasting event in the past. During a call with three colleagues from India, one of them, a recently joined junior team member, struggled to meet the team’s expectations. At one point, the discussion switched from English to their native language. Within seconds, the conversation became heated. Although I couldn’t understand the language being spoken, it was evident that the two senior engineers were providing direct negative feedback to the junior newcomer. In her book, Erin Meyer acknowledges this behavior and points out that ‘it’s not unheard of for an Indian boss to bark criticism at their staff in a way that shocks and silences any Europeans within earshot. But as a foreigner, you should not try this.’

Leading Scale

The leading scale exists to help you understand different leadership styles.

On the leading scale, a distinction is made between two different leadership styles: egalitarian and hierarchical.

As the name suggests, hierarchical leadership is based on a hierarchy where the presence of a boss is essential. In most cases, the boss will issue orders and expect the team to submit to them without any questions asked.

In contrast, egalitarian leadership depicts more of a flat structure where everyone is considered equal. In egalitarian cultures, it is perfectly normal for a line manager to be challenged by their subordinates. In these cultures, everyone has an opinion, and each opinion carries a specific weight.

When I was working in South Africa, I was primarily exposed to the hierarchical leadership style. Reflecting on some of my consulting projects, there was invariably one person calling the shots, often with a fancy title. When this leader said “jump,” the team’s typical response was a simple “how high?” A potential risk of this approach is that decisions might be driven more by individual perspectives than by those of the team. While this risk can be mitigated if the person in charge is exceptionally knowledgeable and experienced, the danger of one-sided decision-making persists, potentially leading to blind spots.

Upon my arrival in the Netherlands, I first encountered an egalitarian form of leadership. Although I observed several individuals in authoritative positions who were prepared to make tough decisions, they almost always sought input from their subordinates first, engaging in open dialogue. After gathering a range of opinions, they were able to make informed decisions and accept the consequences, whether good or bad. This leadership style can be very effective, provided that the person in charge accepts the responsibility of making the final decision. If this responsibility is not acknowledged, it can result in delayed decision-making, adversely affecting the team as they may feel their progress is being stifled. From my personal experience, coming from South Africa, it can also be somewhat frustrating when every new idea must be discussed at every departmental level, leading to prolonged efforts to gain consensus.

When examining my own personal Culture Map, you will notice that I have indicated that Dutch people are extremely egalitarian, whereas Indian people are extremely hierarchical. Somewhere in the middle of the scale, I have plotted British people based on my interactions with my boss who happens to be from the UK.

Therefore, when working with Indian colleagues, it’s important to remember the type of leadership style they are accustomed to. They might very well be used to a person in charge who calls all the shots. This explains why they tend to be quiet in certain settings; they “know their place” and want to show their respect to the leader by keeping quiet and doing what they are told.

In a Dutch corporate setting, you can expect quite the opposite. Here, it is quite normal for any employee, junior or senior, to challenge instructions from the person in charge and give their brutally honest opinion about the topic at hand. In fact, in Dutch culture, it is a good sign when matters are debated because it shows that you have considered different angles, which will likely lead to the best possible outcome. What I find extremely positive about the Dutch arguments that I have witnessed is that everyone is always respectful of one another, and no one talks down to anybody. Although no one really cares who the boss is, they respect everyone and treat everyone equally.

In her book, Erin Meyer points out that “events that took place thousands of years ago continue to influence the cultures in which individuals are raised and formed.” To support her statement, she notes that in some religions, such as Protestantism, the individual speaks directly to God rather than through intermediaries like the priest, the bishop, or the pope. This illustrates why societies where Protestant religions predominate tend to be more egalitarian than those dominated by, for example, Catholicism.

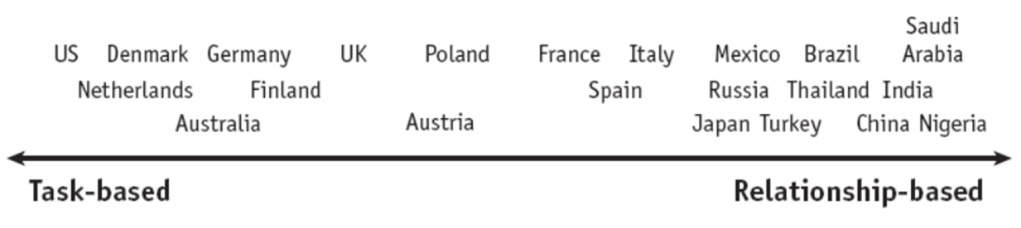

Trusting Scale

The well-known saying “Trust is earned, not given” applies to any cultural setting and the following section will hopefully explain why. In this section, we’ll delve into the two fundamental types of trust—cognitive trust and affective trust—and explore how they shape interactions within different workplace settings and countries.

1. Cognitive trust

Cognitive trust, as the name suggests, originates from the mental processes involved in knowing, learning, and understanding. It is earned when people have confidence in your ability to accomplish tasks effectively. The more consistent you are in completing assigned tasks, the more reliable you become, leading to increased cognitive trust within any workplace setting.

Common examples of countries that operate based on this type of trust system include the United States and Switzerland, where the motto is “business is business.”

2. Affective trust

As the name suggests, affective trust refers to moods, feelings, and attitudes. Unlike cognitive trust, which is based on rational assessment, affective trust comes from within (i.e., the heart) and is earned when you connect with another person on a personal, deeper level—beyond the surface. Sharing a meal together serves as a good example of how you can establish affective trust in any workplace setting.

Some countries, such as China and Brazil, operate on this type of trust system, where “business is personal.”

You may have also heard about so-called peach and coconut cultures:

- People from peach cultures tend to be familiar with the cognitive trust system. They appear soft on the outside, but beneath that surface lies a tougher core. It’s common for them to behave “softly” toward others—for instance, smiling at random people crossing the street or asking personal questions to a stranger on a train. However, once the initial formalities are over, you begin to experience the “hard” part of their personality in an effort to protect their inner selves.

- People from coconut cultures operate on affective trust. Initially, it’s challenging to connect with them—they’re like a tough coconut shell. However, with persistence, you can eventually crack open that shell. Building relationships with these cultures takes time and effort, but once trust is established, you can expect unwavering loyalty from the other person.

Dutch people tend to operate based on cognitive trust (task-based), while Indian people tend to operate based on affective trust (relationship-based). British people lean more toward cognitive trust, although not as strongly as one would expect.

The Trusting Scale (see the picture below) will help you understand how various cultures establish trust. This could be based on relationships and how well you know a person, or on how well you work together and others perform.

Drawing from my own personal experience, I once collaborated with an Indian colleague who faced a deeply tragic period. Although we weren’t particularly close, our entire team rallied to support him during this difficult time. We visited him in the hospital and attended the funeral service. Upon his return to work, I noticed a remarkable increase in his loyalty and commitment to the team. It was evident that we had earned his trust, and he responded to our kindness by giving his absolute best at work.

Concluding, some of my colleagues (who are also managers) travel to India periodically. Upon their return, they often describe the trip as ‘unproductive’ due to all of the social gatherings and fine dining. However, I believe these trips have the potential to be very ‘productive’ in the sense that they can be valuable for fostering even deeper trust within this cultural context. My advice would be to embrace all of the collaboration, and when things are back to normal again, make up for all of the lost focus time. As Erin Meyer wisely puts it, ‘Trust is like insurance—it’s an investment you need to make upfront, before the need arises.’

Scheduling Scale

As I mentioned at the beginning of this blog post, I currently lead a dynamic team comprising seven individuals from around the world. Together, we form a rich tapestry of cultures, including Spanish, Italian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, German, Dutch, and South African.

I will never forget one particular team meeting organized by my Dutch colleague, Richard. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss significant improvements to our solution, which would have a lasting impact on our global user base. Due to unavailability, we were forced to meet in a different part of the building, away from our usual meeting room. Unfamiliar with this area, I decided to be proactive and leave a little earlier, allowing for contingencies in case I got lost. Fortunately, I arrived promptly on the hour, feeling quite pleased with myself, knowing Richard values punctuality.

To my surprise, I wasn’t the first to arrive. On the opposite side of the room sat Hannes, my German colleague, who had actually arrived a couple of minutes earlier! The rest of the team casually arrived several minutes late, seemingly unconcerned about their tardiness. I shifted my attention to Richard, who appeared slightly annoyed by their repeated late arrivals.

Erin Meyer uses the terms linear and flexible when describing how people in different cultures approach time and scheduling:

1. Linear Time

For individuals who fall on the linear-time side of the scale, a typical day unfolds as follows:

- Project steps are tackled sequentially, completing one task before moving on to the next. They focus on one thing at a time, avoiding interruptions.

- The primary emphasis is on meeting deadlines and adhering strictly to schedules.

- Good organization and promptness take precedence over flexibility.

2. Flexible Time

On the other hand, those leaning toward flexible time experience their day differently:

- They approach project steps in a fluid manner, adapting as opportunities arise. They may switch tasks based on changing circumstances.

- Handling multiple things simultaneously is common, and they accept interruptions.

- Their focus lies in adaptability, valuing flexibility over rigid organization.

The Scheduling Scale (see the picture below) illustrates how linear or flexible the cultures being mapped perceive time.

Knowing the above ahead of our next team meeting can help us all understand why certain colleagues behave the way they do. And instead of (some of us) losing our temper and getting annoyed, we might as well have a good laugh about it and recognize the cultural differences at play.

I deepened my understanding when I thought about what might be perceived as “normal” in the various countries represented in our team.

Hannes, hailing from Germany (a first-world country), likely expects most things to proceed according to plan. The “system” rarely disappoints him—for instance, public transport is consistently reliable, allowing him (and his colleagues) to arrive at work punctually each day.

In contrast, Ahmed, coming from Pakistan (a developing country), has grown accustomed to the system letting him down. Irregular public transport means he’s unfazed by colleagues arriving late for meetings; over time, he’s accepted this as perfectly normal behavior.

Personally, I enjoy collaborating with individuals from developing countries—perhaps because I share that background. If we are determined to go somewhere and there is no road, we will build a road despite the cost to pave.

When plotting my colleagues on my personal cultural map, you’ll notice that I’ve placed my Indian colleagues on the extreme right position because they are highly flexible with their time. On the left, I’ve positioned my Dutch colleagues, who are less flexible. My boss from the UK falls somewhere in between, slightly more flexible than the Dutch colleagues but still with a strong preference for linear time. Countries like Germany and Switzerland occupy the most extreme left position.

Advice for navigating cultural differences

Sooner or later, you will start working with people from different backgrounds and cultures. I have had the opportunity to work with many different nationalities, and I am truly grateful for the relationships formed and the lessons learned. Having a multicultural group of colleagues is truly valuable because each culture brings something unique to the table.

The following guidelines (in no particular order) may be helpful to remember when you join a project or team consisting of different cultures.

Value others and seek common ground

To foster connections, identify something you can do to make others feel valued. For instance, on one project, I collaborated with an Indian colleague who had a passion for cricket. Since cricket is also popular in South Africa, I decided to learn and follow the sport. This way, I could discuss the latest cricket action with my colleague and connect with them on a personal level beyond work. As a result of this exercise, your colleague will feel valued because you took the time to learn about something they are passionate about.

Respect other religions and beliefs

Show respect by taking a genuine interest in what other people believe. Ask questions to better understand someone’s perspective. You can also research special days celebrated by different religions and wish your colleagues well on those occasions. Trying local dishes during lunch breaks is another way to demonstrate cultural respect.

Name pronunciation – get it right!

Avoid irritating people by clarifying name pronunciations upfront. If some names are lengthy or difficult to pronounce, ask if there is a shorter version that the person responds to.

Learn basic foreign words

Keep a few basic foreign words in your back pocket for the right occasion. This simple gesture shows that you care about others and that you want to impress them with your foreign vocabulary.

Recap meetings unless otherwise stated

In most Western cultures, it’s considered best practice to verbally recap meetings at the end, followed by a written summary that includes individual action items (shared with all meeting participants). Personally, I’ve developed this habit for very important meetings where accountability is crucial to move forward with a particular initiative.

Respond in a timely manner

When working with people from the U.K. and U.S., it’s essential to respond to their emails and messages within 24 hours, even if you don’t have an immediate answer. You can acknowledge receipt by saying, ‘I confirm receipt of your email and will reply by next Monday.’ A timely response aligns with best practice in these cultures.

Validate assumptions to avoid miscommunication

When dealing with high-context cultures (e.g. India), take responsibility for asking for clarification if you’re unsure about something you’ve heard after reading between the lines.

“Praise in public, criticize in private”

The phrase “Praise in public; criticize in private” is well-known and most frequently attributed to the great football coach, Vince Lombardi. This timeless advice emphasizes the importance of recognizing and celebrating positive contributions openly while addressing corrective feedback privately.

Public praise carries more weight and encourages others to emulate positive behavior. On the other hand, negative feedback is best delivered privately to avoid triggering defensive reactions. This approach allows for clearer communication and increases the chances of learning from mistakes.

Leverage situational leadership

Be willing to leverage situational leadership by adapting your style as and when needed. If appointed as a leader in an egalitarian setting, gain respect by meeting team members at their level. In hierarchical settings, differentiate yourself appropriately (e.g., through dress code). As Erin Meyer states in her book, ‘Increase your ability to work in different ways. Style switching is an essential skill for today’s global manager.’

Establish mutual trust

Regardless of the cultures you’re working with, never underestimate the power of mutual trust. While it may take time to develop, trust is essential for effective work relationships. When collaborating with people from diverse backgrounds, such as coconut cultures (e.g., India), consider extending informal meetings or lunch appointments to build trust. It’s okay if productivity is temporarily affected during these moments; the goal is to establish mutual trust promptly, allowing you to regain focus at work.

Learn to differentiate between the different types of trust

Understanding the trust basis of a culture is crucial. In cognitive trust cultures (e.g., the UK), prioritize getting down to business early in meetings. On the other hand, in affective trust cultures (e.g., China), allocate sufficient time for informal conversation.

Define a clear team culture

In some cases, it may be useful to establish common ground rules upfront by collaborating with your team. For example, consider setting guidelines for meetings, such as arriving no more than 5 minutes late. As a leader, you can use your position to influence this exercise, but it’s important to remember that these ground rules should come from the team. In her book, Erin Meyer clearly recognizes that “most misunderstandings can be avoided by defining a clear team culture that everyone agrees to apply.”

Additional insights from my team members

Towards the end of 2024, I presented the main contents of this blog to my two teams (at the time) to help us better understand each other. Reflecting back, it was a great session with plenty of interaction from all my colleagues (from different backgrounds). I walked away with many new insights, which I wanted to share with you below.

First and foremost, I loved my German colleague’s closing remark: We shouldn’t try to understand another person based solely on their culture. We are all living in an international environment, and two things are important:

- Don’t judge someone based on their culture or try to “categorize” them.

- Do not use your own culture as an excuse for anything.

When talking to people, always choose the individual above the culture.

Secondly, we discussed how the culture scales are based on research and interviews with many different people. They are intended to show tendencies and patterns derived from Erin Meyer’s interactions with various cultures.

I gained the following additional insights after discussing the various scales in depth with my colleagues at work:

- My German (male) colleague highlighted that where one maps oneself on these cultural scales can be influenced by family practices, which may differ from the broader cultural norms.

- My Indian (female) colleague pointed out that communication styles can be influenced by both cultural backgrounds and individual personality traits.

- When I asked three of my Indian colleague where they would plot themselves on the communicating scale, each had a different answer. This highlights the concept of relativity. It would be a big mistake to assume that all Indian people are high-context individuals. It’s not about putting people in a box, but about understanding the relative differences. Within every country, there can be significant variations.

- My Dutch (male) colleague shared that we can give constructive feedback to people we have a genuine relationship with.

- Another Dutch (male) colleague shared that cultural norms are not the only factors at play; company structure also matters. For example, in the Netherlands, ABN Amro Bank is known for being more hierarchical, whereas Rabobank has a flatter structure. My Chinese (male) colleague latched onto this by explaining that in China, state-owned companies are very hierarchical, as the cultural scale suggests, but IT companies tend to have flatter structures.

- In terms of how we view and respond to leadership, it depends on the individual and their personality. My Bangladeshi (male) colleague shared that he always speaks up and questions authority figures if he disagrees, even though he comes from a hierarchical country where this behavior is considered frowned upon.

- Cultural perceptions can shift over time, so what was true many years ago may have changed.

Conclusion

As a closing remark, I highly recommend that you:

- Ask yourself where your colleagues fall on the various cultural scales.

- Create your own personal culture map based on the diverse cultures you are currently working with.

By doing this, you will gain a deeper understanding of your colleagues and learn to appreciate the beauty of cultural differences in the workplace and beyond. And if you’re anything like me, it’s worth remembering the following wise words of Erin Meyer: “Watch more, listen more, and speak less.”

Understanding cultural nuances leads to better interactions across borders and fosters successful collaboration. By embracing these differences, you’ll find that they enrich your professional and personal life in ways you never imagined.

I hope this post gave you some valuable insights! If you found it helpful or have any thoughts to share, please leave a comment below and let me know. Your feedback helps me create better content for you. Don’t forget to hit that like button if you enjoyed reading!

Leave a reply to soggejemiah1989 Cancel reply